Moving Beyond Shame and Rumination

For many of us, especially those carrying trauma, navigating queer identity, or moving between cultures, self-forgiveness feels impossible. We've internalized messages that we're too much or not enough, that our mistakes define us, that we deserve the pain we carry. But what if the voice telling you to keep punishing yourself isn't protection—it's just old pain trying to keep you safe in the only way it knows how?

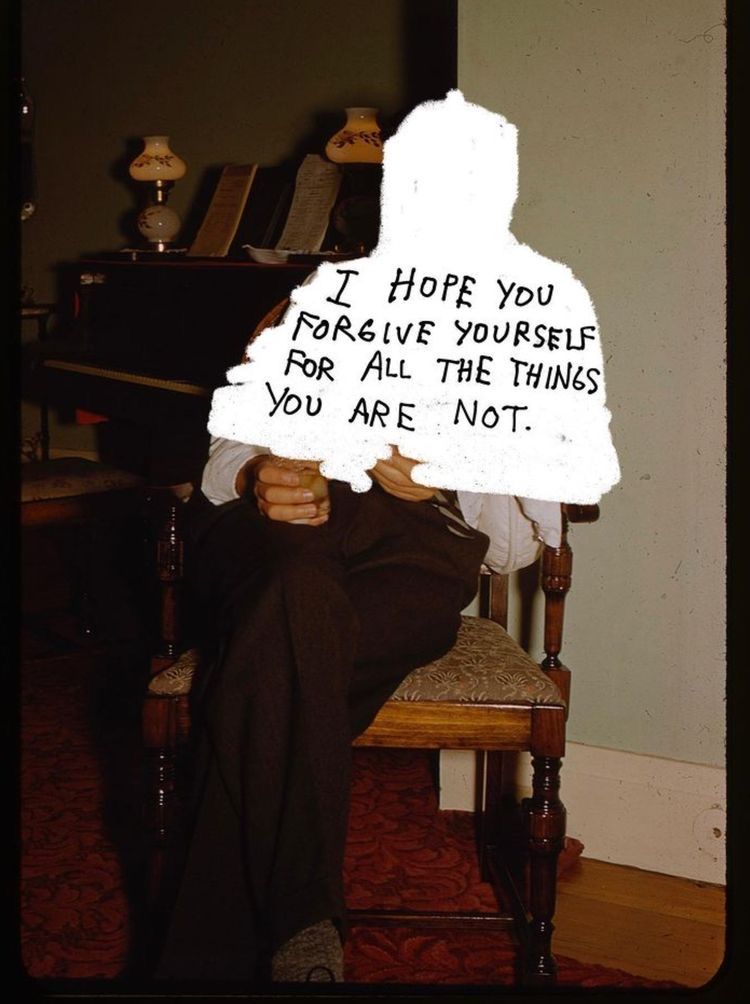

The Radical Act of Self-Forgiveness:

The Hidden Ways We Punish Ourselves

Self-punishment rarely announces itself. It doesn't always look like self-harm or explicit self-hatred. More often, it shows up quietly, woven into the fabric of our daily lives:

Rumination: replaying the same painful moments over and over, analyzing what you should have done differently, keeping the wound fresh and open.

Guilt that never resolves: a constant background hum of "I'm bad," even when you can't pinpoint what you've done wrong.

Shame that lives in your body: the tightness in your chest, the way you make yourself small, the belief that if people really knew you, they'd leave.

Unconscious self-sabotage: pushing away good things because you don't believe you deserve them, or setting yourself up to fail to confirm what you already believe about yourself.

These patterns aren't character flaws. They're survival strategies that once helped you navigate environments where you genuinely weren't safe to make mistakes, to be yourself, or to take up space. But now they're keeping you trapped in a past that no longer exists.

Why Forgiveness Feels Impossible

If self-forgiveness were easy, you'd have done it already. The truth is, forgiveness is complicated, especially when:

You grew up in environments where love was conditional. If acceptance depended on being perfect, making mistakes feels like a moral failure rather than part of being human.

You carry marginalized identities. For queer folks, BIPOC individuals, and others navigating oppressive systems, we've been told our very existence is wrong. Self-forgiveness can feel like agreeing with those who harmed us, or like we're excusing the systems that continue to cause harm.

You believe punishment keeps you safe. There's a deep logic to self-punishment: if you're already punishing yourself, maybe it will hurt less when others inevitably do. If you stay hypervigilant about your mistakes, maybe you won't make them again.

You're afraid forgiveness means forgetting. You worry that if you stop holding yourself accountable through shame and guilt, you'll become the kind of person who hurts others without care.

But here's what's true: shame doesn't make us better people. It makes us smaller, more defensive, less capable of genuine accountability.

What Self-Forgiveness Actually Means

Self-forgiveness isn't about:

- Pretending you didn't hurt anyone

- Excusing harmful behavior

- Bypassing genuine accountability

- Absolving yourself of responsibility

Self-forgiveness is about:

- Accepting that you did the best you could with the resources, knowledge, and nervous system regulation you had at the time

- Recognizing that you are more than your worst moments

- Choosing to learn from your mistakes rather than be defined by them

- Releasing the belief that suffering makes you more worthy

In Internal Family Systems terms, it's about recognizing that the parts of you that made mistakes were trying to protect you or meet needs that felt desperate at the time. They weren't trying to cause harm—they were trying to survive.

The Heartbreaking Truth About Forgiveness

Here's where forgiveness breaks people's hearts open: if you accept that you did the best you could with what you had, you also have to accept that the people who harmed you likely did the same.

This doesn't mean what they did was okay. It doesn't mean you have to reconcile or maintain relationships with people who hurt you. It doesn't minimize the very real pain they caused.

But it does mean releasing the fantasy that they could have been different than they were. It means accepting that your parents, your ex, your former friend—they were limited by their own trauma, their own lack of tools, their own survival strategies.

This is grief work. It's mourning the childhood you deserved and didn't get, the relationship you hoped for but couldn't have, the version of yourself that you imagined if only things had been different.

And it's liberating. Because once you stop waiting for the past to be different, you can finally be present for your life as it actually is.

The Cultural and Queer Dimensions of Self-Forgiveness

For those of us navigating multiple cultural contexts or queer identities, self-forgiveness carries additional layers:

Cultural expectations of perfection can make mistakes feel like family shame, not just personal failure. When you're already representing your community to a world that's quick to judge, the stakes of being human feel impossibly high.

Internalized homophobia and transphobia mean we're often punishing ourselves for the very things that make us beautiful—our queerness, our gender expression, our desires. Self-forgiveness can mean forgiving ourselves for all the years we couldn't accept who we are.

Intergenerational trauma means the shame we carry often isn't even ours. We're holding pain that was passed down, survival strategies from ancestors who needed them to live through genuine danger.

Self-forgiveness in these contexts isn't just personal healing—it's breaking cycles, it's decolonizing our relationship with ourselves, it's choosing a different legacy to pass forward.

Moving Toward Self-Compassion: A Somatic Approach

Self-forgiveness isn't a decision you make once and you're done. It's a practice, a gradual softening, a slow learning to be on your own side.

Here are some entry points:

Notice where shame lives in your body. Do your shoulders curl forward? Does your chest feel tight? Does your stomach clench? Shame has a physical signature. Just noticing it, without trying to change it, is the first step.

Speak to the parts of you that are hurting. Instead of "I'm so stupid for doing that," try "There's a part of me that's really scared I'm not lovable." This creates space between you and the shame.

Ask: What was I trying to protect or provide for myself? Even behaviors you regret were often attempts to meet legitimate needs—for safety, connection, autonomy, pleasure. Can you honor the need even while choosing different strategies now?

Practice the phrase: "I did the best I could." Say it even if you don't believe it yet. Say it especially if you don't believe it yet.

Allow yourself to grieve. Tears aren't weakness—they're your body releasing what it's been holding. Let yourself feel the sadness of what was, without rushing to fix or explain it away.

When Self-Forgiveness Requires Professional Support

Sometimes self-forgiveness feels impossible because the shame is too deep, the trauma too complex, or the patterns too entrenched to navigate alone. That's not failure—that's wisdom.

Working with a trauma-informed, queer-affirming therapist can help you:

- Identify and work with the protective parts of you that believe punishment keeps you safe

- Process the grief of accepting reality as it is

- Build new neural pathways of self-compassion

- Address the underlying trauma that makes mistakes feel so dangerous

- Navigate the cultural and identity layers of shame

Modalities like EMDR, Internal Family Systems, and somatic therapy can help you process shame and guilt at the level where they live—in your body, in your nervous system, in the implicit memories that logic alone can't reach.

You Deserve to Live Free

You don't have to earn your right to self-compassion. You don't have to suffer enough first, or prove that you've learned your lesson, or wait until you're perfect.

You deserve kindness now. Not someday when you've finally healed enough, but now, in your messy, imperfect, still-learning humanness.

Self-forgiveness is the radical act of choosing to be on your own side, of recognizing that you're doing your best, of accepting that being human means making mistakes and that making mistakes doesn't make you unworthy of love.

The truth is, you've been carrying this pain long enough. What if you set it down? What if you let yourself learn from your mistakes without being defined by them? What if you gave yourself the grace you'd offer a friend?

You're not broken. You're not too much. You're not beyond repair.

You're becoming. And you deserve compassion every step of the way.

If you're struggling with shame, guilt, or self-punishment and need support navigating the path toward self-forgiveness, trauma-informed therapy can help. At Queer Joy Therapy in Toronto, I offer a safe, affirming space for 2SLGBTQ+ individuals to process shame, heal from trauma, and build a more compassionate relationship with themselves. Book a free consultation to start your healing journey.